I start teaching a course on Principles of Economics to kids at a Genwise camp today, and life is so, so good.

The start of a course is always exciting – there’s curiosity (on both sides) about what the experience is going to be like. And on my side of the fence, there is also a sense of curiousity about where the course will end up, and what route we will end up having taken to get there.

My method to teach principles of economics isn’t really a method. There are about six principles that I teach (incentives matter | costs matter | trade matters | prices matter | externalities matter | time matters), along with three big picture questions (what does the world look like? | why does it look the way it does? | what can we do to make the world a better place?). If you have taught a course like this, you may have a slightly different list, but I would be surprised (and extremely intensely curious to know more!) if it was wildly different.

But the subject really comes alive when I help the students realize that ye to bas intro tha. One, it is the application of these principles that truly matters. And two, the penny really and truly drops when you realize that these principles are applicable, always and everywhere, to everything that we all do in our lives.

In that sense, economics really and truly is the study of “how to get the most out of life”.

And beginning today, I have the privilege of doing this for a new batch of students, over the next five days. As I was saying, life is so, so good!

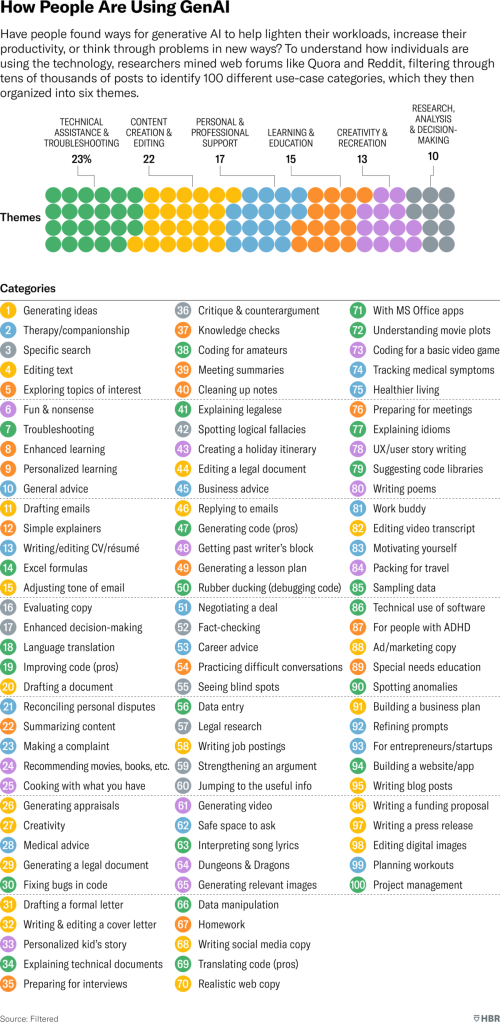

One thing that I am going to try in this class is the use of AI as a complement to my teaching. I have used AI in class before, of course, but not to the extent that I am planning on using it this time around. I’ll let you know how it pans out, of course, but for now, here’s a custom GPT , built by me, that I am planning on using. If you pay for access to ChatGPT-4, I would be most grateful if you kick the tires a l’il bit, and give me feedback about how it is working out for you.

This custom GPT was built by modifying Ethan Mollick’s excellent “Devil’s Advocate” prompt. If you are an educator and haven’t tried out his excellent prompts, you really should!

Finally, you might be wondering about the title of today’s post. Surely I meant to write “Nothing like teaching”, you might be thinking.

Life is a non-zero sum game, y’see – you learn best when you teach others!